LESSON FOUR

The Personal is Political

“Ordinary community members are who made SANKOFA what it is today, not the elite, not the bourgeois.”

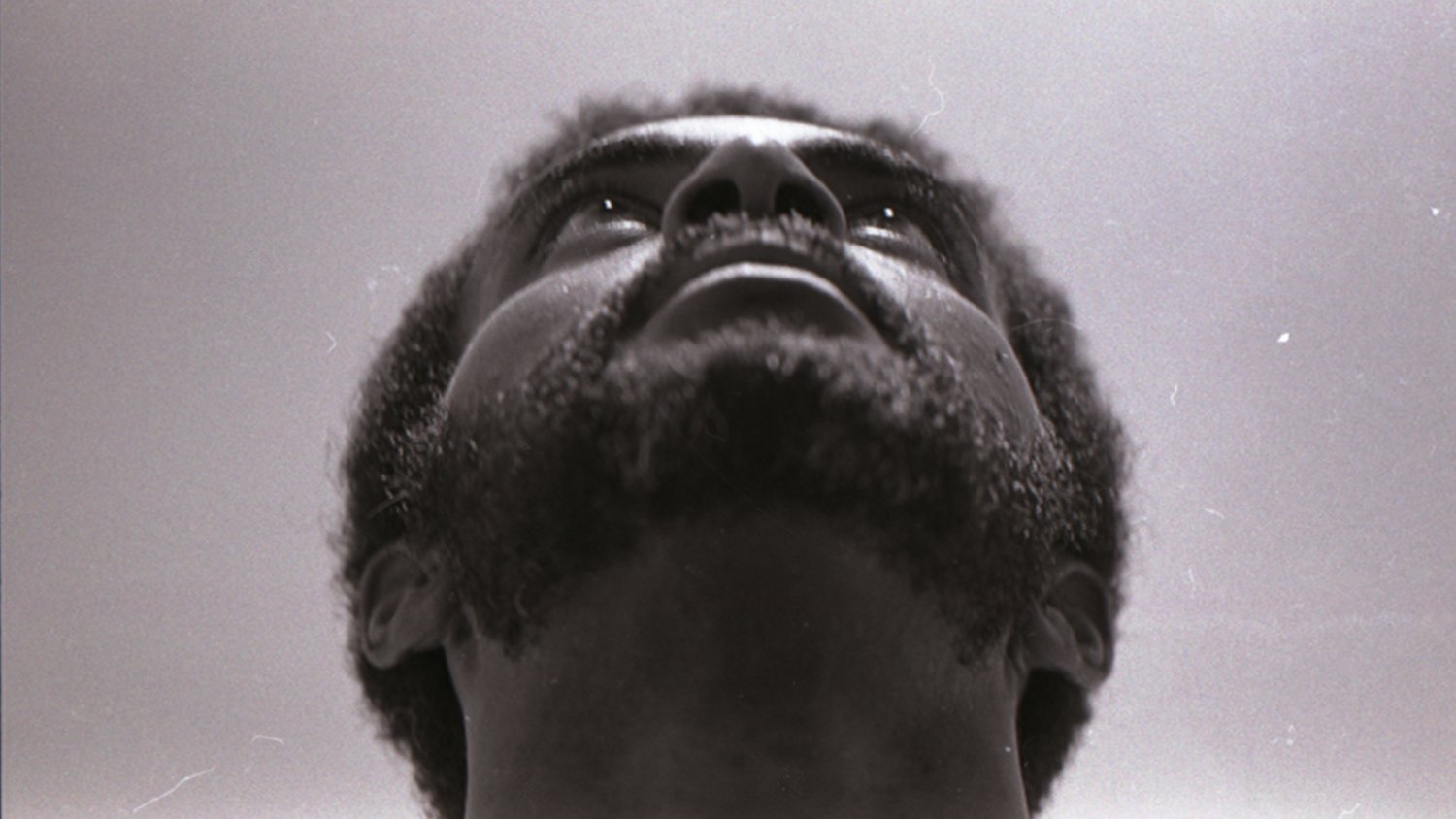

When director Haile Gerima speaks, people all over the world listen. And when he talks about his most famous film, SANKOFA, his words become a rallying cry for artists around the globe. For more than 40 years, his charge to himself, other creatives and the hundreds of film students who have passed through his Howard University classroom is to take control of their narratives and get their stories to the masses by any means necessary. It is a mission that has met its moment.

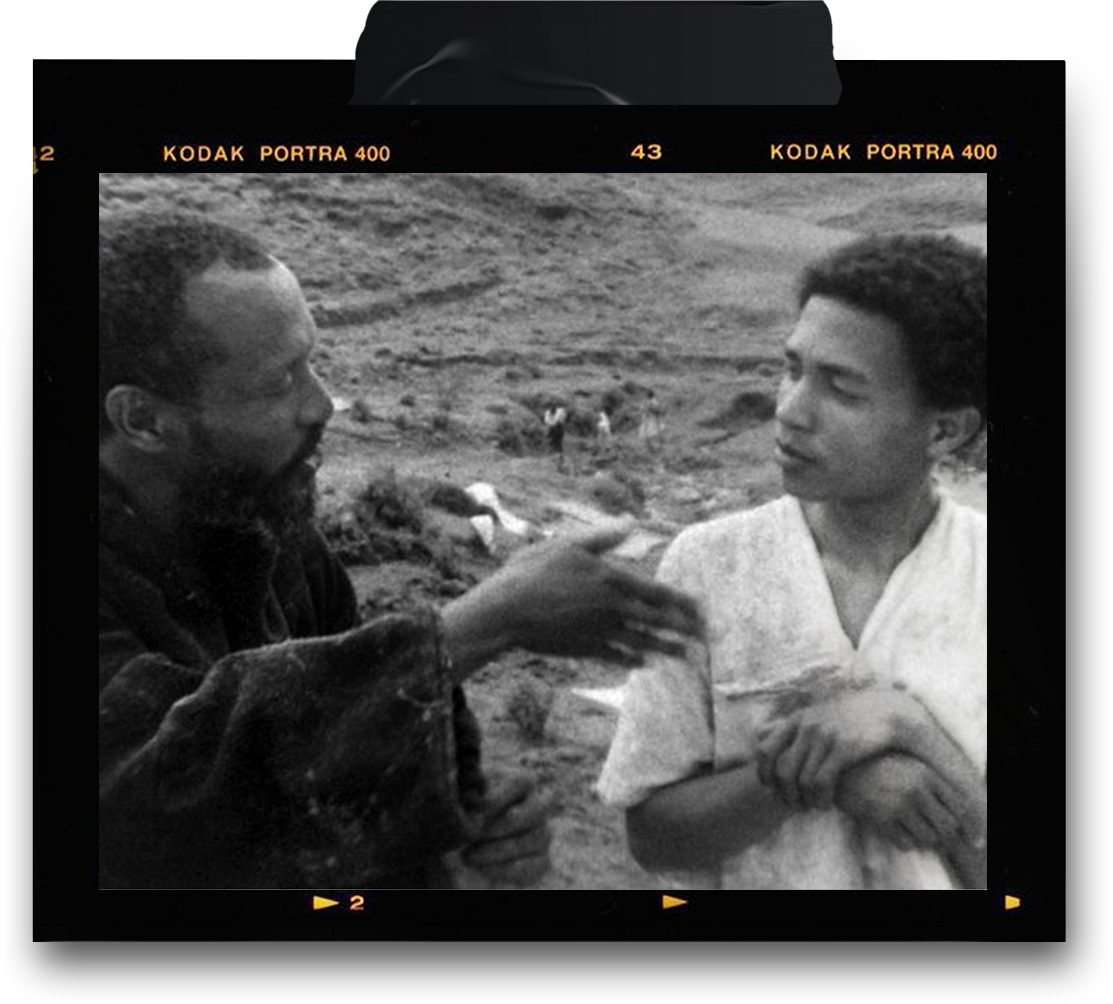

Arriving in the United States from Ethiopia as a theater student in 1967, Haile Gerima followed in his father’s footsteps, a dramatist and playwright. Gerima studied acting in Chicago before entering the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, where his exposure to Latin American films inspired him to mine his cultural legacy. After completing his thesis film, BUSH MAMA (1975), Gerima received international acclaim with HARVEST: 3000 YEARS (1976), an Ethiopian drama that won the Grand Prize at the Locarno Film Festival.

Following the award-winning ASHES & EMBERS (1982) and the documentaries WILMINGTON 10 – U.S.A. 10,000 (1978) and AFTER WINTER: STERLING BROWN (1985), Gerima filmed his epic, SANKOFA (1993). SANKOFA received glowing reviews while in competition at the Berlin International Film Festival. However, distribution of the film in traditional theaters proved a much more challenging task, though not impossible. Before the release of SANKOFA, Gerima had already set out on his own journey — one that included becoming an exhibitor and distributor of independent Black films, side by side with his wife Shirikiana Gerima. With the help of the grassroots African-American community, they sustained two years of theatrical distribution for SANKOFA. Their desire to see collective success among Black filmmakers has motivated them to create independent cinema for decades.

Following the award-winning ASHES & EMBERS (1982) and the documentaries WILMINGTON 10 – U.S.A. 10,000 (1978) and AFTER WINTER: STERLING BROWN (1985), Gerima filmed his epic, SANKOFA (1993). SANKOFA received glowing reviews while in competition at the Berlin International Film Festival. However, distribution of the film in traditional theaters proved a much more challenging task, though not impossible. Before the release of SANKOFA, Gerima had already set out on his own journey — one that included becoming an exhibitor and distributor of independent Black films, side by side with his wife Shirikiana Gerima. With the help of the grassroots African-American community, they sustained two years of theatrical distribution for SANKOFA. Their desire to see collective success among Black filmmakers has motivated them to create independent cinema for decades.

“Be history makers, not spectators,” says Gerima when speaking about how he believes Black people should show up in the world. “Everyone isn’t going to like the art you create, and that’s ok; you aren’t making it for everyone.”

For decades, followers of Haile Gerima’s work have been drawn to his unique method of explaining film narrative and intrigued by his rebellious attitude towards the traditional systems of making and criticizing films. His lectures often mirror the call and response experience seen in Black churches. Whether speaking about collective success, liberation or resistance – the audience’s physical and verbal affirmations make clear that his message resonates deeply with those who understand and embrace his canon of work.

“Be history makers, not spectators,” says Gerima when speaking about how he believes Black people should show up in the world. “Everyone isn’t going to like the art you create, and that’s ok; you aren’t making it for everyone.”

For decades, followers of Haile Gerima’s work have been drawn to his unique method of explaining film narrative and intrigued by his rebellious attitude towards the traditional systems of making and criticizing films. His lectures often mirror the call and response experience seen in Black churches. Whether speaking about collective success, liberation or resistance – the audience’s physical and verbal affirmations make clear that his message resonates deeply with those who understand and embrace his canon of work.

LESSON FOUR

Liberated Territory and Methods

Gerima continues to distribute and promote his films, such as TEZA (2008), which won the Jury and Best Screenplay awards at the Venice International Film Festival. He also lectures and conducts workshops in alternative screenwriting and directing both within the U.S. and internationally.

The Gerima’s bookstore in Washington D.C. is known as ‘Liberated Territory,’ a space where creatives are allowed to unshackle themselves from the binding colonial construct that dictates what art matters and which artists should be celebrated. Founded in 1996 with a desire to create a communal space where marginalized voices take center stage, the bookstore has become sacred ground for self-expression, offering film screenings, book signings and artist showcases to the community. “We wanted people to learn about Black people in Black spaces designed for intellectual engagement. We wanted to create a liberated territory,” says Gerima. A family affair where you can find Mr. and Mrs. Gerima, as well as their adult children, the Sankofa bookstore is an extension of his work as a young filmmaker on the campus of the University of California in Los Angeles in the 1960’s.

Then, just as now, it was essential to Gerima carve out safe spaces within systems when possible and outside of systems when necessary to explore and create. When speaking about critics Gerima reminds audiences, “No one has gone into our cinematic form. We have critics who do not know how to read our films. Our critics used conventional barometers to judge our work. Even when trying to speak about the work we did with other filmmakers at UCLA, they create a caste system. We were people who were made who we were by the Black community.”

Speaking about the audience-spectator relationship that his cinematic form achieves, Gerima explains that, “We have been inundated for over 100 years by Hollywood to be passive spectators. My idea is active spectatorship that culminates into a historical making. The individual, the community and the collective community enters into the psychological idea of wanting to be a history maker or recuperating or snatching our capacity to be history makers.”

Gerima continues, “The framing is the struggle. Movies can be made about anybody and be used as an instrument to enslave us. My idea is to break down that whole idea, that formula cinema, attack it, and destroy it. While I make my movies, I am fully aware of what I want to be doing; I want to tear down the oppressive form. If not, no one is going to be liberated, including the filmmaker, I.”

Gerima has championed work for over 45 years that is ‘innovatively independent’ from mainstream cinema. He has also encouraged other Black filmmakers to do the same. “Most especially the young filmmakers do not see strength in communal or collective existence,” says Gerima. “They just think they’re going to conquer the world as individuals. There is no world like that. In cinema, it’s always [been], even in Hollywood, a collective surge.”

His point of view is shared by filmmakers such as Ava DuVernay, who has expressed her struggle to work simultaneously independent of and within the traditional Hollywood filmmaking model. “The fact that so few people had seen Ashes and Embers before our media collective ARRAY re-distributed it is a travesty. It’s a masterpiece and deserves to be a part of every film school curriculum in this country. Not including it is cinema segregation, and we’re done waiting on others to acknowledge and distribute the work of the geniuses in our communities, we’ll do it ourselves, and we will do it spectacularly.”

Haile Gerima teaches us, through his words and his art, that there must be new movement and new learning with each generation.

Then, just as now, it was essential to Gerima carve out safe spaces within systems when possible and outside of systems when necessary to explore and create. When speaking about critics Gerima reminds audiences, “No one has gone into our cinematic form. We have critics who do not know how to read our films. Our critics used conventional barometers to judge our work. Even when trying to speak about the work we did with other filmmakers at UCLA, they create a caste system. We were people who were made who we were by the Black community.”

Speaking about the audience-spectator relationship that his cinematic form achieves, Gerima explains that, “We have been inundated for over 100 years by Hollywood to be passive spectators. My idea is active spectatorship that culminates into a historical making. The individual, the community and the collective community enters into the psychological idea of wanting to be a history maker or recuperating or snatching our capacity to be history makers.”

Gerima continues, “The framing is the struggle. Movies can be made about anybody and be used as an instrument to enslave us. My idea is to break down that whole idea, that formula cinema, attack it, and destroy it. While I make my movies, I am fully aware of what I want to be doing; I want to tear down the oppressive form. If not, no one is going to be liberated, including the filmmaker, I.”

Gerima has championed work for over 45 years that is ‘innovatively independent’ from mainstream cinema. He has also encouraged other Black filmmakers to do the same. “Most especially the young filmmakers do not see strength in communal or collective existence,” says Gerima. “They just think they’re going to conquer the world as individuals. There is no world like that. In cinema, it’s always [been], even in Hollywood, a collective surge.”

His point of view is shared by filmmakers such as Ava DuVernay, who has expressed her struggle to work simultaneously independent of and within the traditional Hollywood filmmaking model. “The fact that so few people had seen Ashes and Embers before our media collective ARRAY re-distributed it is a travesty. It’s a masterpiece and deserves to be a part of every film school curriculum in this country. Not including it is cinema segregation, and we’re done waiting on others to acknowledge and distribute the work of the geniuses in our communities, we’ll do it ourselves, and we will do it spectacularly.”

Haile Gerima teaches us, through his words and his art, that there must be new movement and new learning with each generation.

”In this early work, Gerima strove for something more than an individual story, achieving a bracing polemic and an impassioned narrative of bleak and haunting beauty.” —Shannon Kelley, UCLA Library, Film and Television Archive

LESSON FOUR

Activity — Liberated Viewing

While writing about SANKOFA, director Nijla Mumin, a former student of Haile Gerima, said “Gerima encouraged us to break and subvert that paradigm. To create Black characters that were rich with inner turmoil, who resisted, struggled, who sought intimate relationships and who possessed sensuality. It is on this foundation that Sankofa rests.”

Like close reading of a text, close viewing of a film is the act of carefully and purposefully viewing and reviewing a film clip in order to focus on what the filmmaker is trying to convey; the choices the filmmaker has made; the role of images, narration, editing and sound; and the purpose of the film.

This activity ensures that participants become critical viewers of film content and can use it to understand complex issues both in and outside of the film. Learners can choose any clip from the film SANKOFA for this activity. This exercise can be completed by individuals, in a small group or as a large group.

LESSON FOUR

Activity — Liberated Viewing

While writing about SANKOFA, director Nijla Mumin, a former student of Haile Gerima, said “Gerima encouraged us to break and subvert that paradigm. To create Black characters that were rich with inner turmoil, who resisted, struggled, who sought intimate relationships and who possessed sensuality. It is on this foundation that Sankofa rests.”

Like close reading of a text, close viewing of a film is the act of carefully and purposefully viewing and reviewing a film clip in order to focus on what the filmmaker is trying to convey; the choices the filmmaker has made; the role of images, narration, editing and sound; and the purpose of the film.

This activity ensures that participants become critical viewers of film content and can use it to understand complex issues both in and outside of the film. Learners can choose any clip from the film SANKOFA for this activity. This exercise can be completed by individuals, in a small group or as a large group.

Step 1: Choose a Scene

View a scene from the film SANKOFA. After watching the clip, learners should write down their general thoughts and reactions. Group leaders and teachers can feel free to prompt participants with questions such as: What stands out for you? What resonated with you? What questions do you have?

Step 2: Focused Viewing

Films are layered media involving story, character development, images, sound and pacing. When making a movie, there are many people involved in each of these areas who contribute to the end result of the finished movie, and they each view the film through their own lens. For instance, a composer will watch a movie, looking for opportunities to evoke emotion through sound, whereas an editor may make choices that speak to the pace of the film. Learners will view the chosen scene and only use ONE lens while doing so. Use the prompts below to guide thinking and take notes.

Sound

Focus on the music in the series as well as the sound effects. What do you notice? What stands out to you? Does the music make you feel joyful, sad, angry, hopeful?

Storyline/Historical Facts

How is the story unfolding? What historical facts are portrayed in this film? Are you learning new information?

Human Behavior

How do you see the range of human behavior represented in this film? Where do you see the themes of humanity, power or privilege? What is the purpose of this film? Is it to teach, entertain or do something else?

Editing

Pay attention to the way that the images and videos are edited or ‘cut’ together. Does the director make lots of quick cuts? Does the filmmaker spend more time on some scenes than others before transitioning to a new scene? Would you describe the editing as fast-paced, slow-paced or even-paced? Does the pacing have an impact on the emotional response of the viewer? If so, how?

Images

Focus on the visual experience; do not pay attention to the audio (you may choose to watch in silence). What do you notice? What choices did the filmmaker make as they relate to color and movement? How does the director frame the images? Are there several people in most of the scenes or are the characters often alone? What is the impact of these choices? Could other choices have been made?

Step 3: Discussion

- What motivations might the filmmaker have? How are these manifested in the scene?

- Were there examples of inner turmoil, resistance, struggle, intimacy or sensuality in the scene as mentioned at the beginning of this activity? If so, what were they and how were they used in the scene?

- What did you already know about this topic? How might your prior knowledge of the topic change how you experienced the scene?

- Who/what was included in the message of the scene? Who/what was left out?

Step 1: Choose a Scene

View a scene from the film SANKOFA. After watching the clip, learners should write down their general thoughts and reactions. Group leaders and teachers can feel free to prompt participants with questions such as: What stands out for you? What resonated with you? What questions do you have?

Step 2: Focused Viewing

Films are layered media involving story, character development, images, sound and pacing. When making a movie, there are many people involved in each of these areas who contribute to the end result of the finished movie, and they each view the film through their own lens. For instance, a composer will watch a movie, looking for opportunities to evoke emotion through sound, whereas an editor may make choices that speak to the pace of the film. Learners will view the chosen scene and only use ONE lens while doing so. Use the prompts below to guide thinking and take notes.

Sound

Focus on the music in the series as well as the sound effects. What do you notice? What stands out to you? Does the music make you feel joyful, sad, angry, hopeful?

Storyline/Historical Facts

How is the story unfolding? What historical facts are portrayed in this film? Are you learning new information?

Human Behavior

How do you see the range of human behavior represented in this film? Where do you see the themes of humanity, power or privilege? What is the purpose of this film? Is it to teach, entertain or do something else?

Editing

Pay attention to the way that the images and videos are edited or ‘cut’ together. Does the director make lots of quick cuts? Does the filmmaker spend more time on some scenes than others before transitioning to a new scene? Would you describe the editing as fast-paced, slow-paced or even-paced? Does the pacing have an impact on the emotional response of the viewer? If so, how?

Images

Focus on the visual experience; do not pay attention to the audio (you may choose to watch in silence). What do you notice? What choices did the filmmaker make as they relate to color and movement? How does the director frame the images? Are there several people in most of the scenes or are the characters often alone? What is the impact of these choices? Could other choices have been made?

Step 3: Discussion

- What motivations might the filmmaker have? How are these manifested in the scene?

- Were there examples of inner turmoil, resistance, struggle, intimacy or sensuality in the scene as mentioned at the beginning of this activity? If so, what were they and how were they used in the scene?

- What did you already know about this topic? How might your prior knowledge of the topic change how you experienced the scene?

- Who/what was included in the message of the scene? Who/what was left out?

“Often we are made to disconnect our nerve endings, our antennas, meaning in spiritual terms, and therefore miss out on all kinds of possible communications with our past ancestors. We’re not listening to the bones from the past that are trying to talk to us, even if they traveled like an arrow and tried to jar open our spiritual memory. I think the one thing that this film project enlightened me on is one’s ability to recall past ancestors. That is, even for simple and daily invocation, in order to say thank you. This is a very important philosophical principle of the ancestral referential way of co-existence, not only for Black people but for the world. I grew up with these invocations. My mother never ate anything without invoking, without saying thank you, and she’s even Catholic on top of that. She always said thank you as she threw some of the food around for the ancestors to eat also. Even on a personal level, my journey to give birth to the film story of SANKOFA has connected me. In spiritual terms, where I was disconnected, it has made me more centered and partially fulfilled.”