We don’t have to wait for somebody to tell our story,

we can do it ourselves.”

Being savagely taken from one’s homeland and family is a violation beyond imagination.

Enslaved Africans were transported primarily from the west coast of the African continent to Europe, the Caribbean, South America, North America and the British Isles beginning in 1500 and continuing through the mid to late 1800s. Although England and the United States both legally abolished the international slave trade in 1807, illegal slave ships still arrived in the United States as late as 1860, and even into the 1890s in some parts of South America.

This unfathomable journey, the transatlantic trafficking of humans from the African continent to nations throughout the world, bore witness to more than 12.5 million people being stripped from their families and communities and sold to slave owners desiring unpaid labor for their personal wealth-building schemes.

According to estimates from the website Slave Voyages, Spain’s colonies received over one million humans, while almost nine million people landed on the shores of Brazil and other Portuguese colonies. Over three million men and women were sent to British imperial holdings aboard slave ships, while the Dutch and Danish colonies received over half a million souls. French colonies demanded 1.3 million and more than 305,000 people would directly land on the shores of the United States, in addition to many that initially landed in the Caribbean.

Key theme

Community

Objectives

- Draw evidence from informational texts to describe the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on today’s society

- Record and post an oral history

- Understand how communication tools, such as drumming, have been used by cultures around the world to keep stories alive for generations

Everyone has a story to tell. Collectively, these stories create the history of the lands on which we all live.

Scroll down to view links to three activities in this lesson, plus additional background information that will help inform learning.

LESSON ONE

Activities

Activity 3:

Storytelling Through Music

Activity 3:

Storytelling Through Music

LESSON ONE

How desperate were enslavers?

LESSON ONE

How desperate were enslavers?

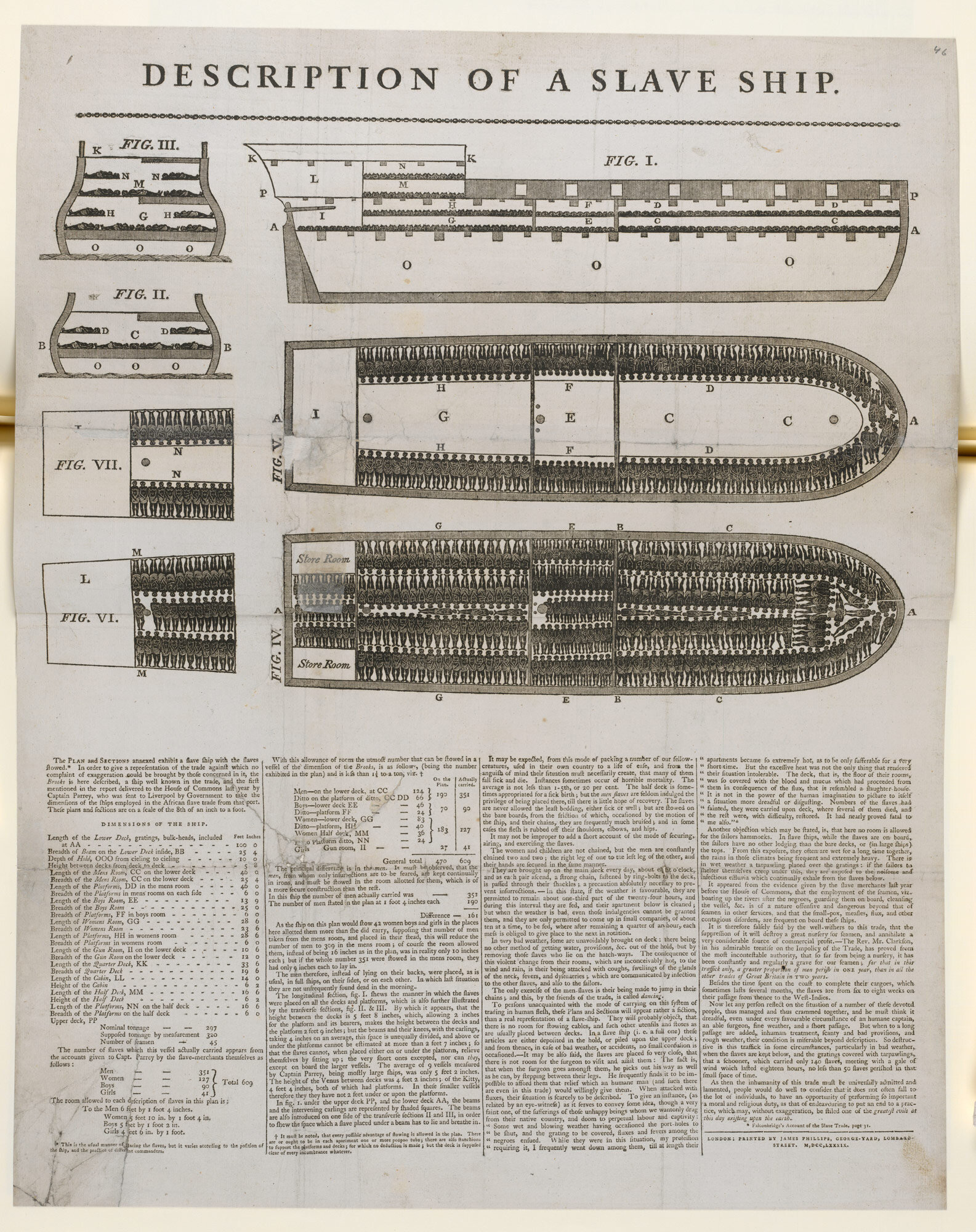

The amount of greed shown in the transport of captured human cargo can be seen in the graphic drawings of the slave ship Brooks. According to a 1788 account by abolitionist William Elford, in an effort to maximize the number of trafficked humans onto the enormous vessel, the idea of placing people head to toe was sometimes abandoned and men were placed so that one person’s head was between another person’s thighs, thus maximizing the length of 6 feet and width of 16 inches allowed for each adult male.

Expert Knowledge

The expert knowledge held by African men and women in the areas of farming technology, architecture, medicine and engineering made them a desirable commodity for planters and landowners seeking fortunes in new worlds. “People of African descent come from ancient, rich and elaborate cultures that created a wealth of technologies in many areas,” explains Dr. Sydella Blatch. Writing about scientific achievements in ancient African civilizations, Blatch draws attention to the omission of the technological genius found on the African continent, remarking, “Sadly, the vast majority of discussions on the origins of science include only the Greeks, Romans and other whites. But in fact most of their discoveries came thousands of years after African developments. While the remarkable [B]lack civilization in Egypt remains alluring, there was sophistication and impressive inventions throughout ancient sub-Saharan Africa as well.” As detailed in the iconic book by Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, the unique skills these talented individuals brought with them from their homeland had been developed for centuries, a fact that could not be denied by those looking to profit from their abilities.

An Investment Worth Protecting

Enslaved humans were so profitable that institutions around the globe found ways to protect the investments of the enslavers through financial instruments, including insurance policies and stock in slaving companies.

In The Price for Their Pound of Flesh, historian Daina Ramey Berry notes that value was assigned to enslaved African men, women and even young children. They were considered commodities from birth, through their lives and even after death. “In addition to burying, selling and transporting enslaved bodies for medical research, enslavers took out life insurance policies on children at age nine and ten to protect their investments.” Analyst Michael Ralph, creator of the database Treasury of Weary Souls, explains that “after the slave trade to the US was outlawed in 1808, Africans were smuggled into the country (a tricky process), they were bred (which depended on the human life cycle), and they were rented (so the people who treated them as property could make as much money as possible). People who rented slaves insured them so that these valuable assets would not be destroyed while in someone else’s possession.”

In a modern-day act of resistance, a California state law pushed by then-Senator Tom Hayden (D-Santa Monica) and signed into law by Gov. Gray Davis in 2000, requires all insurance companies doing business in the state to publicly release information about policies they or their predecessor firms wrote insuring slave owners for losses if slaves died or ran away. Learners can view the names of the insured enslaved here.

LESSON ONE

The GU272

Not only did individual people looking for financial gain benefit from enslavement, but so did institutions, including some of the most highly regarded universities in the United States.

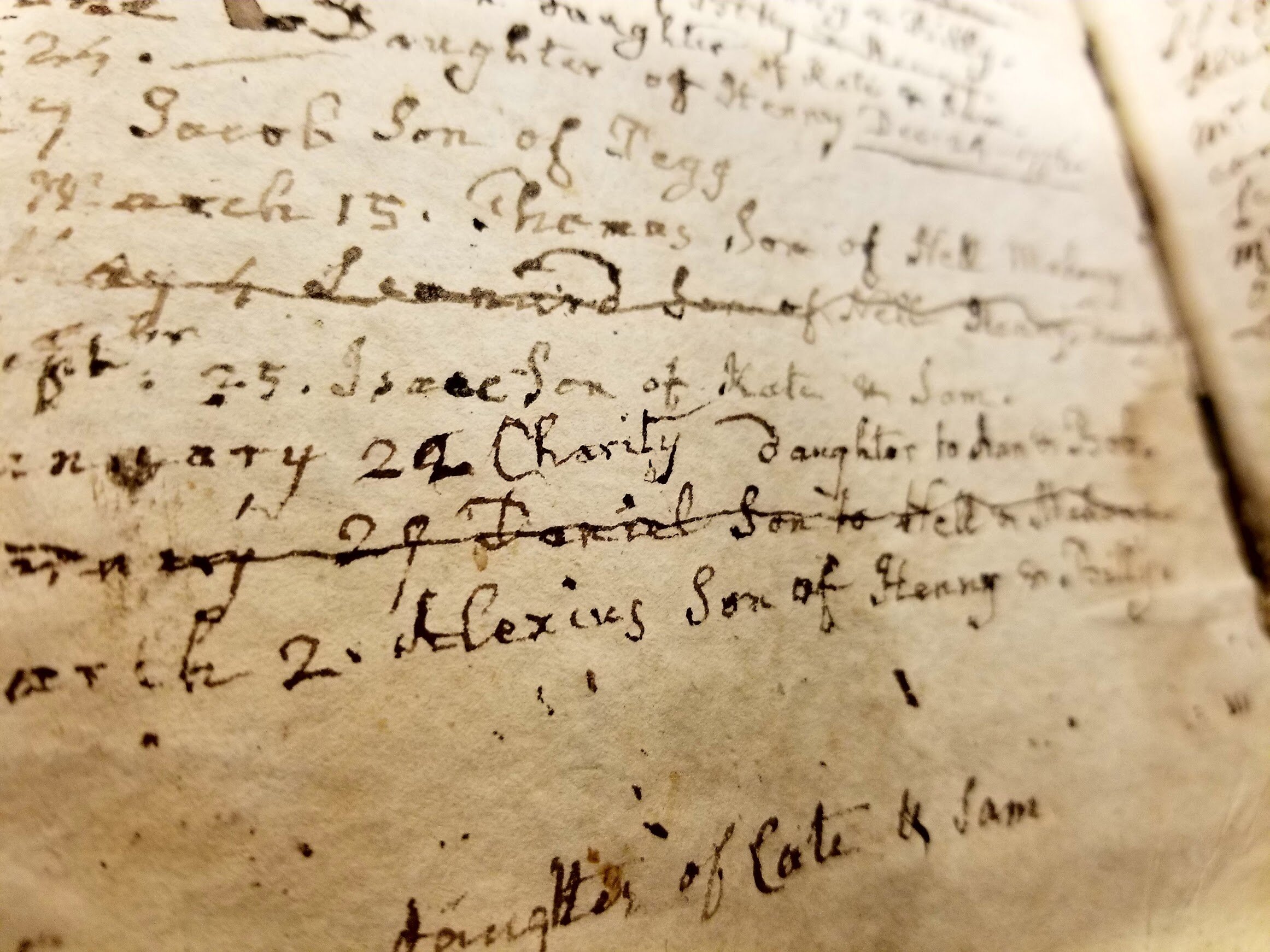

Search the hashtag #GU272 online and learners can see hundreds of posts, articles and conversations by the descendants of the enslaved women, men and children of the Maryland Jesuits’ 1838 slave sale that helped keep the doors of Georgetown University open for business. Due to recent outcry and resistance efforts from descendants, students and employees, a residence hall on campus has been renamed to Isaac Hawkins Hall and an archive has been dedicated to amplifying the plight of the nearly 300 men, women and children who were sold. Previously the building had been called Mulledy Hall after Thomas F. Mulledy, the provincial superior and later president of the school, who orchestrated the 1838 sale.

The new honoree and namesake of the building, Mr. Isaac Hawkins, was the first enslaved person named on the original list compiled in preparation for the 1838 sale.

LESSON ONE

The GU272

Not only did individual people looking for financial gain benefit from enslavement, but so did institutions, including some of the most highly regarded universities in the United States.

Search the hashtag #GU272 online and learners can see hundreds of posts, articles and conversations by the descendants of the enslaved women, men and children of the Maryland Jesuits’ 1838 slave sale that helped keep the doors of Georgetown University open for business. Due to recent outcry and resistance efforts from descendants, students and employees, a residence hall on campus has been renamed to Isaac Hawkins Hall and an archive has been dedicated to amplifying the plight of the nearly 300 men, women and children who were sold. Previously the building had been called Mulledy Hall after Thomas F. Mulledy, the provincial superior and later president of the school, who orchestrated the 1838 sale.

The new honoree and namesake of the building, Mr. Isaac Hawkins, was the first enslaved person named on the original list compiled in preparation for the 1838 sale.

LESSON ONE

The Griot

The practice of remembering history through storytelling can be found in every community where humans have ever lived. In many West African cultures, the griot or storyteller profession is hereditary and coveted in the community. This person is responsible for memorizing and retelling genealogies, family histories and stories about members of the community. As we see in the beginning of the film, the griot plays a very important role. He is considered a guardian of the culture and he is respected for his wisdom. The first written account of the word griot is found in the 14th-century writings of traveler Ibn Battuta while visiting Mali. Present-day scholars have used the word to describe a vast number of storytellers. Scholar Thomas A. Hale describes the duties of griots — and their female counterparts, griottes — as historians, genealogists, poets, teachers, exhorters, town criers, reporters and more, depending on the needs of the time.

What was life like for enslaved Africans before, during and after enslavement?

The life stories of thousands of formerly enslaved individuals have been recorded and published for centuries. This collection of narratives located at the Library of Congress is called Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938. These narratives, mostly told to and written by non-Black writers, provide a glimpse into what life was like for descendants of the Africans who survived the harrowing journey through the Middle Passage through the stories they passed down.

LESSON ONE

The Griot

The practice of remembering history through storytelling can be found in every community where humans have ever lived. In many West African cultures, the griot or storyteller profession is hereditary and coveted in the community. This person is responsible for memorizing and retelling genealogies, family histories and stories about members of the community. As we see in the beginning of the film, the griot plays a very important role. He is considered a guardian of the culture and he is respected for his wisdom. The first written account of the word griot is found in the 14th-century writings of traveler Ibn Battuta while visiting Mali. Present-day scholars have used the word to describe a vast number of storytellers. Scholar Thomas A. Hale describes the duties of griots — and their female counterparts, griottes — as historians, genealogists, poets, teachers, exhorters, town criers, reporters and more, depending on the needs of the time.

What was life like for enslaved Africans before, during and after enslavement?

The life stories of thousands of formerly enslaved individuals have been recorded and published for centuries. This collection of narratives located at the Library of Congress is called Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938. These narratives, mostly told to and written by non-Black writers, provide a glimpse into what life was like for descendants of the Africans who survived the harrowing journey through the Middle Passage through the stories they passed down.

But there are also narratives of enslavement still remembered on the African continent.

Go ka nu dze ge woyina.

(On which shores are we going to land?)

Go ka nu dze ge woyina.

(On which shores are we going to land?)

Those lyrics, in the form of a story, were passed down from one generation to the next by elders in southeastern Ghana, once known as the ‘Old Slave Coast’ and documented by historian Anne C. Bailey in her book African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Beyond the Silence and the Shame. They come from the songs heard by those remaining on land as a slave ship sailed into the distance with captives.

“This song is like a wailing, a lamentation — a song that simultaneously captures the deep grief and anxiety of those fateful moments of capture and enslavement in a way that mere words cannot,” says Bailey. It is no wonder that this story was repeated orally for hundreds of years before finally being written down and archived.