LESSON ONE • ACTIVITY ONE

Say It Loud

Examining Narratives Using Primary and Secondary Sources

LESSON ONE • ACTIVITY ONE

Say It Loud

Examining Narratives Using Primary and Secondary Sources

OBJECTIVE: Draw evidence from informational texts to better understand the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on communities.

PARTICIPANTS WILL: Review narratives of enslaved individuals and discuss the intersections between the lives of the formerly enslaved and current-day issues.

The pressure on Black filmmakers not to address their humanity in motion pictures is enormous. They are told in one way or another, again and again, that their grandmother’s story is not commercial, meaning not important enough to be told on film.”

The Resistance Narrative:

Who was Omar Ibn Sa’id?

Source: Library of Congress

Learn More: Visit the Omar Ibn Said Collection

Omar Ibn Sa’id told his own story through his autobiography.

“According to his autobiography, and to articles written about him in the American press while he was still alive, he was a member of the Fula ethnic group of West Africa who today number over 40 million people in the region extending from Senegal to Nigeria. In the interviews he gave during his lifetime he stated that he was born in a place called Futa Toro “between the two rivers” referring to the Senegal and the Gambia rivers that separate those two countries. His father, who was a wealthy man, was killed in an inter-tribal war when he was five, and Omar and his family had to move away to another town. In his autobiography, Omar Ibn Said writes that as he grew older he sought knowledge in Bundu, an area in Senegal today that had historically been controlled by another ethnic group, the Mande people, until the Muslim Fulas conquered the region in the second half of the 17th century. Omar ibn Said writes that in Bundu he studied under his own brother Sheikh Muhammad Said, as well as two other religious leaders and “continued seeking knowledge for twenty five years.” He then returned to his own town and lived there for another six years, until a “big army” came “that killed many people,” captured him and sold him to a man who took him “to the big Ship in the big Sea.” After sailing for a month he arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, where he was bought by a man called Johnson, who apparently was cruel to him. So he escaped, was captured and landed in jail in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he spent 16 days. That is where he began writing in Arabic on the walls of his jail, and where he was discovered and eventually taken into the household of Jim Owen and his brother John Owen, the Governor of North Carolina (1828-1830) with whom he remained until his death in his late eighties.”

Source: Library of Congress

Learn More: Visit the Omar Ibn Said Collection

“According to his autobiography, and to articles written about him in the American press while he was still alive, he was a member of the Fula ethnic group of West Africa who today number over 40 million people in the region extending from Senegal to Nigeria. In the interviews he gave during his lifetime he stated that he was born in a place called Futa Toro “between the two rivers” referring to the Senegal and the Gambia rivers that separate those two countries. His father, who was a wealthy man, was killed in an inter-tribal war when he was five, and Omar and his family had to move away to another town. In his autobiography, Omar Ibn Said writes that as he grew older he sought knowledge in Bundu, an area in Senegal today that had historically been controlled by another ethnic group, the Mande people, until the Muslim Fulas conquered the region in the second half of the 17th century. Omar ibn Said writes that in Bundu he studied under his own brother Sheikh Muhammad Said, as well as two other religious leaders and “continued seeking knowledge for twenty five years.” He then returned to his own town and lived there for another six years, until a “big army” came “that killed many people,” captured him and sold him to a man who took him “to the big Ship in the big Sea.” After sailing for a month he arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, where he was bought by a man called Johnson, who apparently was cruel to him. So he escaped, was captured and landed in jail in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he spent 16 days. That is where he began writing in Arabic on the walls of his jail, and where he was discovered and eventually taken into the household of Jim Owen and his brother John Owen, the Governor of North Carolina (1828-1830) with whom he remained until his death in his late eighties.”

PRIMARY SOURCES

Primary sources are from the time period in which a person lived. They can be accounts of a person’s life, like the story of Omar Ibn Said who you just read or William Wells Brown’s after he escaped slavery when he wrote Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave: Written by Himself in 1847. They could also be written or dictated by someone, like I, Rigoberta Menchú a “first-person account of the brutality of the Guatemalan government and ruling class toward indigenous Guatemalans.” Although Nobel Peace Prize laureate Rigoberta Menchú dictated her story to anthropologist Elisabeth Burgos-Debray who transcribed it, it is still considered a primary source or first-hand story.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Secondary sources are ones written later by historians that explain a past event or person’s life based on primary sources. Secondary sources include things like biographies. The word ‘story’ is tricky because sometimes it is used to mean fiction but other times, especially when referring to a life story, it means non-fiction.

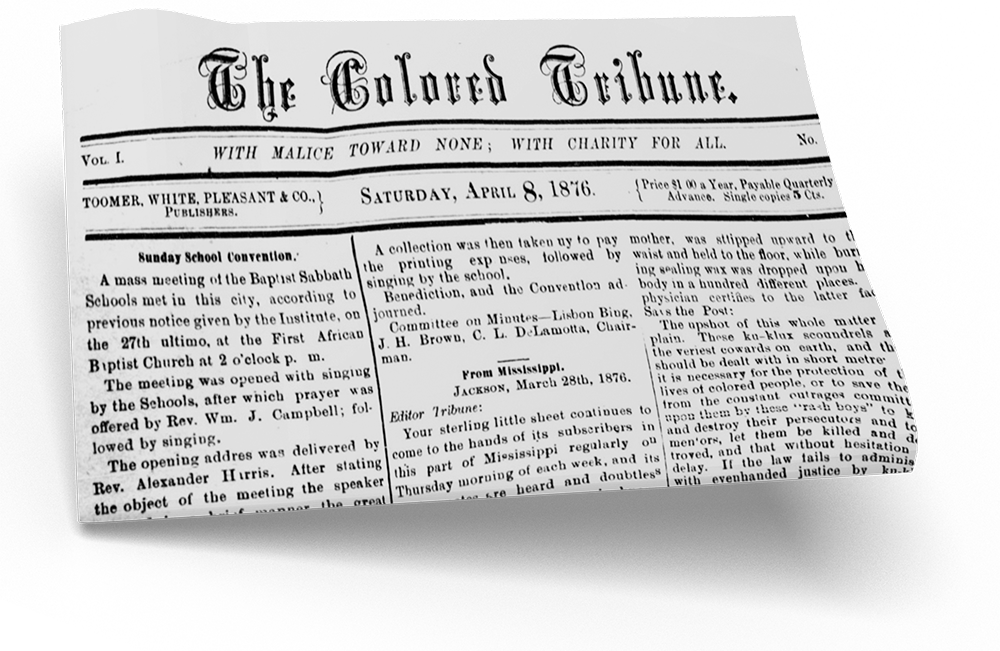

Sometimes, a document can be both a primary and secondary source. Take for example this 1876 article in the historic Savannah, Georgia Black newspaper The Colored Tribune.

Scroll to the bottom of the center column, beginning with the section that reads, “The Wilmington (N.C.) Post has a long account…” The article references an act of violence against African Americans and then calls for acts of resistance. The recounting of the story serves as secondary source information.

The call to action against the Ku Klux Klan makes it a primary source highlighting how Black people were asked to respond to acts of terror a decade after the end of the Civil War. “It is a game at which both sides can play,” writes the author. “And the whites have vastly more to lose than the negroes. Let the negroes prepare to defend themselves and wives and families by every means at their command…”

Sometimes, a document can be both a primary and secondary source. Take for example this 1876 article in the historic Savannah, Georgia Black newspaper The Colored Tribune.

Scroll to the bottom of the center column, beginning with the section that reads, “The Wilmington (N.C.) Post has a long account…” The article references an act of violence against African Americans and then calls for acts of resistance. The recounting of the story serves as secondary source information.

The call to action against the Ku Klux Klan makes it a primary source highlighting how Black people were asked to respond to acts of terror a decade after the end of the Civil War. “It is a game at which both sides can play,” writes the author. “And the whites have vastly more to lose than the negroes. Let the negroes prepare to defend themselves and wives and families by every means at their command…”

Keeping the Story Alive

Men, women and children brought to Europe, Cuba, South America, North America and the British Isles and sold into the construct of slavery kept the memories and histories of their homelands alive for many generations. While it is often difficult to piece together the full life story of individuals who were enslaved since the records kept about them by their enslavers are often limited, many stories have endured and can now be found online, at libraries and in museums. Primary and secondary sources can help us know more about people’s journeys and experiences as they cultivated farmlands, built cities, lived as both enslaved and free people and raised families.

Examine the Life of

Mr. Venture Smith

PROCEDURES:

- 1. Read a narrative that is a primary source of enslavement, the excerpt from Mr. Venture Smith’s narrative.

- 2. Read a secondary source of African enslavement, also a narrative, choosing one from the website Enslaved.org.

- 3. Evaluate the differences between the two types of narratives.

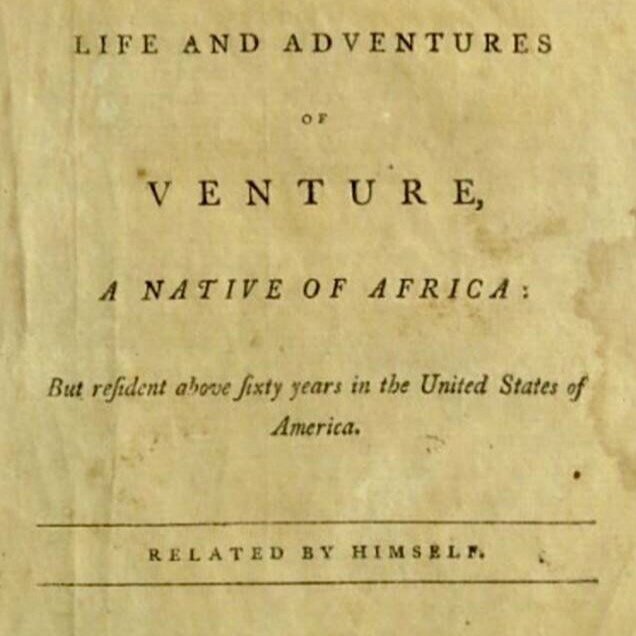

Examining the Life of Mr. Venture Smith (Primary Source)

Image: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Planting the sugar-cane." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1800 - 1899.

The following passage comes from A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa, another personal account written by a formerly enslaved person, Venture Smith (birth name Broteer). As a child, he was taken away from his home in Africa when his father’s kingdom was attacked and sold into the transatlantic slave trade from the port of Anomabu, in the modern-day country of Ghana. His family had named him Broteer, but a sailor on the slave-trading ship that took him to America considered him his private business venture, and accordingly called him “Venture.”

The slave ship Charming Susanna collected newly enslaved people, including Venture, in Anomabu in 1739, and sold most of them on the island of Barbados. Venture was taken to the mainland of North America, where he was enslaved in Rhode Island, New York and Connecticut. Although we mainly associate slavery with the American South, the northern states also allowed slavery during the colonial period and in some cases for many years after the American Revolution. Despite receiving harsh treatment during his enslavement, Venture managed to accumulate enough money working on his own time to purchase his freedom in 1765. After that, he continued working to purchase the other members of his family so he could set them free as well. He published A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture in 1798, when he was a free man. He died in Connecticut in 1805.

Excerpt from A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, by Venture Smith

“A detachment from the enemy came to my father and informed him, that the whole army was encamped not far out of his dominions, and would invade the territory and deprive his people of their liberties and rights, if he did not comply with the following terms. These were to pay them a large sum of money, three hundred fat cattle, and a great number of goats, sheep, & asses.

My father told the messenger he would comply rather than that his subjects should be deprived of their rights and privileges. …The enemy pledged their faith and honor that they would not attack him. On these he relied and therefore thought it unnecessary to be on his guard against the enemy. But their pledges of faith and honor proved no better than those of other unprincipled hostile nations; for a few days after a certain relation of the king came and informed him, that the enemy … meditated [planned] an attack upon his subjects by surprise, and that probably they would commence their attack in less than one day, and concluded with advising him, as he was not prepared for war, to order a speedy retreat of his family and subjects…

The army of the enemy was large… consisting of about six thousand men. Their leader was called Baukurre. After destroying the old prince, they decamped [left] and immediately marched towards the sea, lying to the west, taking with them myself and the women prisoners. … The enemy had remarkable success in destroying the country wherever they went. For as far as they had penetrated, they laid the habitations [homes] waste and captured the people. The distance they had now brought me was about four hundred miles. All the march I had very hard tasks imposed on me, which I must perform on pain of punishment. I was obliged to carry on my head a large flat stone used for grinding our corn, weighing … as much as 25 pounds; besides victuals [food], mat and cooking utensils. Though I was pretty large and stout of my age, yet these bur[d]ens were very grievous to me, being only about six years and an half old.”

“The invaders then pinioned [tied up] the prisoners of all ages and sexes indiscriminately, took their flocks and all their effects, and moved on their way towards the sea.…They then went on to the next district which was contiguous to the sea, called in Africa, Anamaboo. The enemies provisions were then almost spent, as well as their strength. The inhabitants knowing what conduct they had pursued, and what were their present intentions, improved the favorable opportunity, attacked them, and took enemy, prisoners; flocks and all their effects. I was then taken a second time. All of us were then put into the castle, and kept for market. On a certain time I and other prisoners were put on board a canoe, under our master, and rowed away to a vessel belonging to Rhode-Island, commanded by capt. Collingwood, and the mate Thomas Mumford. While we were going to the vessel, our master told us all to appear to the best possible advantage for sale. I was bought on board by one Robertson Mumford, steward of said vessel, for four gallons of rum, and a piece of calico, and called VENTURE, on account of his having purchased me with his own private venture. Thus I came by my name.

Thus I came by my name. All the slaves that were bought for that vessel's cargo, were two hundred and sixty.

AFTER all the business was ended on the coast of Africa, the ship sailed from thence to Barbadoes. After an ordinary passage, except great mortality by the small pox, which broke out on board, we arrived at the island of Barbadoes: but when we reached it, there were found out of the two hundred and sixty that sailed from Africa, not more than two hundred alive. These were all sold, except myself and three more, to the planters there.”

Examining the Life of Mr. Venture Smith (Primary Source)

Image: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Planting the sugar-cane.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1800 – 1899.

The following passage comes from A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa, another personal account written by a formerly enslaved person, Venture Smith (birth name Broteer). As a child, he was taken away from his home in Africa when his father’s kingdom was attacked and sold into the transatlantic slave trade from the port of Anomabu, in the modern-day country of Ghana. His family had named him Broteer, but a sailor on the slave-trading ship that took him to America considered him his private business venture, and accordingly called him “Venture.”

The slave ship Charming Susanna collected newly enslaved people, including Venture, in Anomabu in 1739, and sold most of them on the island of Barbados. Venture was taken to the mainland of North America, where he was enslaved in Rhode Island, New York and Connecticut. Although we mainly associate slavery with the American South, the northern states also allowed slavery during the colonial period and in some cases for many years after the American Revolution. Despite receiving harsh treatment during his enslavement, Venture managed to accumulate enough money working on his own time to purchase his freedom in 1765. After that, he continued working to purchase the other members of his family so he could set them free as well. He published A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture in 1798, when he was a free man. He died in Connecticut in 1805.

Excerpt from A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, by Venture Smith

“A detachment from the enemy came to my father and informed him, that the whole army was encamped not far out of his dominions, and would invade the territory and deprive his people of their liberties and rights, if he did not comply with the following terms. These were to pay them a large sum of money, three hundred fat cattle, and a great number of goats, sheep, & asses.

My father told the messenger he would comply rather than that his subjects should be deprived of their rights and privileges. …The enemy pledged their faith and honor that they would not attack him. On these he relied and therefore thought it unnecessary to be on his guard against the enemy. But their pledges of faith and honor proved no better than those of other unprincipled hostile nations; for a few days after a certain relation of the king came and informed him, that the enemy … meditated [planned] an attack upon his subjects by surprise, and that probably they would commence their attack in less than one day, and concluded with advising him, as he was not prepared for war, to order a speedy retreat of his family and subjects…

Image: Map of West Africa, 1743, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

The army of the enemy was large… consisting of about six thousand men. Their leader was called Baukurre. After destroying the old prince, they decamped [left] and immediately marched towards the sea, lying to the west, taking with them myself and the women prisoners. … The enemy had remarkable success in destroying the country wherever they went. For as far as they had penetrated, they laid the habitations [homes] waste and captured the people. The distance they had now brought me was about four hundred miles. All the march I had very hard tasks imposed on me, which I must perform on pain of punishment. I was obliged to carry on my head a large flat stone used for grinding our corn, weighing … as much as 25 pounds; besides victuals [food], mat and cooking utensils. Though I was pretty large and stout of my age, yet these bur[d]ens were very grievous to me, being only about six years and an half old.”

“The invaders then pinioned [tied up] the prisoners of all ages and sexes indiscriminately, took their flocks and all their effects, and moved on their way towards the sea.…They then went on to the next district which was contiguous to the sea, called in Africa, Anamaboo. The enemies provisions were then almost spent, as well as their strength. The inhabitants knowing what conduct they had pursued, and what were their present intentions, improved the favorable opportunity, attacked them, and took enemy, prisoners; flocks and all their effects. I was then taken a second time. All of us were then put into the castle, and kept for market. On a certain time I and other prisoners were put on board a canoe, under our master, and rowed away to a vessel belonging to Rhode-Island, commanded by capt. Collingwood, and the mate Thomas Mumford. While we were going to the vessel, our master told us all to appear to the best possible advantage for sale. I was bought on board by one Robertson Mumford, steward of said vessel, for four gallons of rum, and a piece of calico, and called VENTURE, on account of his having purchased me with his own private venture. Thus I came by my name.

Thus I came by my name. All the slaves that were bought for that vessel’s cargo, were two hundred and sixty.

AFTER all the business was ended on the coast of Africa, the ship sailed from thence to Barbadoes. After an ordinary passage, except great mortality by the small pox, which broke out on board, we arrived at the island of Barbadoes: but when we reached it, there were found out of the two hundred and sixty that sailed from Africa, not more than two hundred alive. These were all sold, except myself and three more, to the planters there.”

Discussion Questions:

- 1. What surprised you about Venture Smith’s account of the slave trade?

- 2. What effects did the presence of European slave traders on the coast have on African communities?

- 3. What important questions about the transatlantic slave trade does this section of Venture Smith’s account leave unanswered?

- 4. Can Mr. Smith’s decision to tell his own story in the 1700s be described as an act of resistance? If so, why?

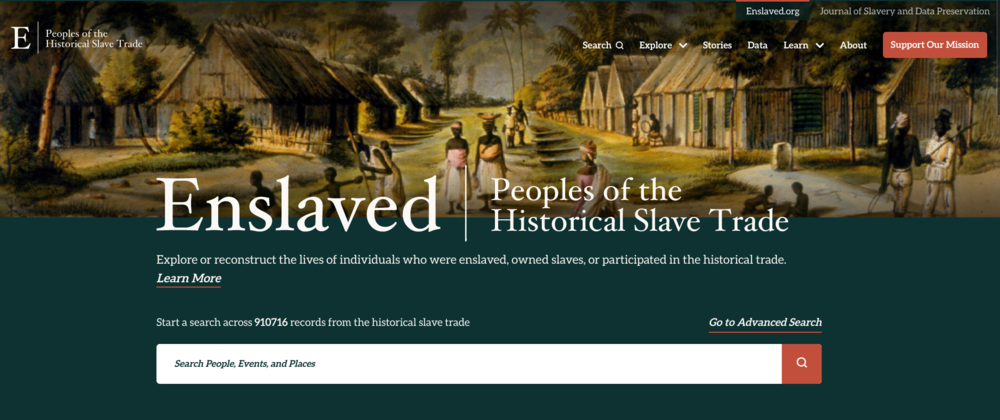

Read a secondary source of African enslavement

Secondary sources are ones written later by historians that tell stories based on primary sources. Secondary sources include things like biographies. The website Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade (Enslaved.org) contains the true stories of the lives of dozens of enslaved people from across the Americas.

“Through these biographies, we can better understand the complexities of people’s lives and the role of slavery and freedom in shaping them,” say Steven Niven and Kristina Poznan, two of Enslaved.org’s historians.

PROCEDURES:

- 1. Go to https://enslaved.org/stories and choose one person’s story to read.

- 2. In the “Find a Story By Title or Keyword” search bar, you can search for a story about a person from a specific place by typing “Barbados” or “North Carolina” etc., or you can browse to find one to read.

Reflection Questions:

- 1. What did you learn about the experience of enslavement and the life of the person you read?

- 2. How were the person’s experiences similar or different to Venture Smith’s?

- 3. Was it different to read about Venture Smith’s story from his own recollections (a primary source) vs. a story written by a historian later (a secondary source)? What’s the value in each approach?

- 4. Is there someone in your family or community whose story should be recorded and preserved so that future generations can read about it?